Into No-Man’s land

As a result of the 6 days war in June 1967 Israel had occupied the Sinai peninsula, which had been egyptian territory. Between 1967 and 1970 and during the Yom Kippur war in october 1973 Egypt in a coalition with other Arab countries tried to gain back the territory lost. However, the Arab countries did not succeed and the Sinai cease fire line stayed where it was: at the Suez Canal. During the Yom Kippur war, after initial advances far into the Sinai peninsula the Israeli army had driven back the Egyptian army across the Suez Canal and encircled in the City of Suez. The city was heavily destroyed and only quick ceasefire agreements saved the Egyptians from the total loss of their army and even deeper humiliation.

Eventually, in a 13 days meeting in September 1978 in Camp David, US president Jimmy Carter brokered a deal between Israeli president Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat. The deal entailed a peace process including a stepwise retreat of the Israelis from the Sinai. When we arrived in Egypt in April 1981, the border line between the two enemies was close to the famous monastery of St. Catharine, in the middle of the Sinai. The monastery was in the No-Man’s land, the demilitarised zone between the lines. And we were eager to go there.

When we arrived in Suez the city still was marked by war. Only the buildings along the main road were partly rebuilt. Many were riddled by bullet holes or the upper floors were in ruins. Behind the main road the buildings in the side streets were destroyed and the rubble only left small passages. Nobody at the bus station seemed to know how to continue into the Sinai. Eventually a taxi left us at a rebuilt hotel where the new toilets already were broken again. But people were friendly and helpful and eventually we found a shop to change some money (there were no ATM at the time). A taxi driver knew about a bus into the interior of the peninsula in the morning and was willing to pick us up at 6 am.

The bus is supposed to leave at a place called El Schatt at the other side of the canal. The driver not only comes on time but also stops at a couple of shops to convince us to buy some provisions for our adventurous undertaking. We had not even thought of that. He left us at a ferry about 10 km north of town. While big freighters float through the desert we can indeed make out a bus on the other side. While we wait for the ferry to start operating a seemingly endless convoy of ships passes. Japanese car carriers, freighters, container ships, small tankers, also a passenger ship and the egyptian Navy all pass north-bound. The bigger ships lead the convoy. Later the direction changes and the south-bound traffic is allowed to pass. In the break between the two directions a floating bridge is installed to let traffic cross the canal. Most of the people crossing the bridge are soldiers, but the bus coming in from the south also brings two backpackers. A swing bridge up north, the only one ever built for cars and the railroad, was destroyed in the wars. A soldier immediately approaches when I take pictures but I pretend not to understand what he is talking about.

The ferry across the canal

There is nothing here besides a little shack selling snacks and a couple of army tents. We regret that we did not buy more provisions at the shops the taxi driver showed us. We just have what we need for the time while we wait for the bus. In particular there is no mineral water.

We were at the ferry at 7 in the morning. Eventually we extract from somebody that the bus will leave before 3 pm. After we get to the other side a driver arrives around 9.30. The bus leaves at 12. It does not go to our final destination but to a place called Wadi Feiran, from where we have to find our own means of transport.

Ice cream seems to have a tremendous attraction for the Egyptians. Just before our bus is packed to the brim a tinkling ice cream seller drives up outside - and instantly has a considerable pull on almost all passengers. The soldiers stand smiling in small groups around the cart and spend the last of their pay on buying a comrade an ice cream. The ones in front willingly pass on the portions they just bought to the ones behind - a picture of harmony. Hard to believe that there are people who put these peaceful men behind machine guns and teach them to shoot down unknown others. I would love to taste the ice cream, but I am afraid to catch the egyptian sickness, diarrhoea, on this packed bus.

My but is already hurting when the bus finally leaves. Besides the driver there is an assistant and the ticket seller. The latter, a funny little chap with a patchy, stubbly beard, bald and without teeth, manages to squeeze his enormous belly through the full bus and handles a confusing variety of tickets and battered bank notes with the agility of a juggler his balls. For the negligible amount of 55 Piaster we each get 10 tickets without knowing exactly where we will go.

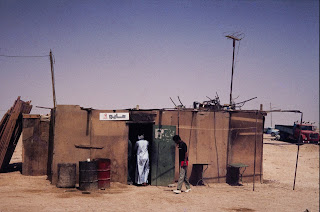

Truck stop in the Sinai

The first part of the road is paved and the bus advances quickly. Sand walls covered with barbed wire, the old Israeli fortifications, are still visible. We pass burnt out vehicles and tanks, abandoned tank chains and other military junk. Big signs warn from leaving the road.

Abou Zenima

After an hour we reach a pit stop built from corrugated iron and cardboard. Everybody except us leaves the bus. From here on the road is a sandy track. The bus leaves an impressive trail of dust behind. Even the locals close the windows, which does not improve the air quality inside, however.

We arrive in a place called Abou Zenima, a symbol of desolation. Long rows of stone barracks fenced in against the sandy hot desert wind by barbed wire. Sand is everywhere. In the shack selling snacks you first have to blow the dust out of the glasses. Sand grinds between the teeth. The numbers on the barracks gives the place the look of a concentration camp. The few people wandering around are perceptible by the sound of grinding sand. No loud conversations like everywhere else in Egypt. After the bus arrives people sit around apathetically as if they were morally crushed by the sand stone cliffs surrounding the village. After a short break we continue.

The route follows a sand covered narrow gage railway. Some of the rails are twisted like corkscrews. A Diesel engine is left in the middle of the desert, dust covered and forgotten. Then we pass a burnt out train of tank wagons. It must have been an easy target for the air force in this open terrain. The landscape becomes wilder, rock faces in all colours between white, yellow, red and dark brown. Shadow exists only when wind or a flood has carved out a shallow cave from the rock. A few sad scrubs cling to the cliffs. After a long descent a military post with painstaking inspection of the passports. Then we arrive in the next village, Abou Rodéis.

Modern little houses look abandoned. In the background rattles an oil rig. A shack sells everything you want…. dust covered cans of coke, stale bread and tea. A few scrubs whither away in the shadow of the houses. I can make one happy with some liquid from my body. My whole right side aches from the bus ride. I eat a flat bread and grapefruit from our precious provisions. It helps to survive the next bit of bus ride. I hope we arrive in Feiran soon and dream of an eiderdown bed and warm food.

The bus stops again, in the middle of the desert. They unload our backpacks. We have to get off here. They point at a dirt track disappearing in the desert to the left and tell us to wait for a taxi or another bus here. It is about half an hour before sunset. At the road side a corrugated iron shack with a couple of guys. They don’t pay any attention to us. Next to it a four-wheel drive without wheels and a dusty old russian truck. From further away the sound of a generator. A many prays in the dust, his face points in the direction of Mecca. I sit down next to a couple of guys in front of what might have once been a garage. One of the guys offers me a cup of sweet tea. It is another 130 km of desert track to our destination. The couple of cars passing by go in the wrong direction.

It is almost dark now. One of the guys in an orange overall understands a couple of words in English and explains that there might be a bus early in the morning. Well, we have a tent and there is some water left. A couple of battered trucks pass but don’t stop.

Then a Toyota jeeps arrives and turns into the dirt track. We wave but they don’t stop. No, they stop, a guy hops out and talks to one of the loiterers at the shack. I run there and ask: "Wadl Feiran?"

“Yes”

They take us along. We throw our bags and ourselves on the open back. The driver comes back and asks again to make sure: “Wadi Feiran? St. Catharine,..?". So they even go as far as our final destination. We cannot believe our luck and completely forget to ask about the price. But although this might turn out annoying the joy about our luck prevails. The ride in the airy open back of the truck is a pleasure.

Another break in Feiran. The darkness does not allow to see what supposedly is a magnificent and rich oasis. A guy in a richly decorated kaftan, almost blond hair and European traits arrives and gives our drivers a cordial welcome. But he only speaks Arabic. We are invited into a Bedouin tent for tea. It turns out that our drivers are agricultural engineers working at an irrigation project at St. Catharine.

The road gets worse. Sometimes the jeep brakes so hard that we are thrown against the back of the driver’s cabin. A trailer is left abandoned and unlit in the middle of the track. Another police check. Even with a torch we have problems to find our passports. The officers wait patiently. Then we arrive at a settlement.

We stop at a solid and clean looking building. We ask the driver for a place to stay. He says something about the airport, 20 km away and expensive. Then they usher us back on the truck and we climb up a steep hill. We stop. In a smoky room the driver introduces us to a group of tough looking guys. They offer us tea again. We can get a room in one of their barracks. It is empty except a couple of mattresses and a petrol lamp. For an egyptian pound a night they also bring us tea and water. They also offer food but we politely decline. The engineers refuse to accept any payment for the ride. Highly satisfied about our easy conquest of the Sinai peninsula we fall asleep on our mattresses.

We wake up in a morning of blinding light. Our hosts bring us water and we take in the scenery. Neat and clean stone houses surrounded by low walls dot the valley. Then and there groups of cypress trees. The background of rugged mountains lets the tiny houses appear like toys. Our hosts point out a cafeteria and we go there for a breakfast of goat cheese, bread and tea. And bottles of coke. Again there is no mineral water. So we take the risk and fill our canteens from the water of one of the wells which gush out of the rocks at various points of the valley.

The monastery of St. Catherine is one of the oldest operating monasteries in the world. It was built between 548 and 565. It also has one of the world’s oldest surviving libraries. The fortified structure is built around the burning bush, which supposedly was seen by Moses. It is still there. 2285 m high mount Musa, 2 km away, was where Moses received the 10 commandments. The monastery is the seat of the Archbishop of Sinai, who nevertheless prefers to reside in Cairo. He is part of the eastern orthodox church. The massive fortifications around the church protected the site for 1500 years. In 2017, an attack by ISIS ended at the checkpoint which gives access to St. Catherine and the monastery. One police officer was killed and several wounded.

The monastery of St. Catharine

One of the gardens

We have heard that the monks of the monastery are welcoming to visitors but that it takes sometimes quite a time to be let in. So we patiently wait at the entrance. However, when the door finally opens after one and a half hours of waiting somebody tells us that we cannot get in. The monks have to pray. It is the holy week. We offer some bakschisch, but to no avail.

The stairs up to the top of Mount Musa

The church on the top of Mount Musa

We heartily curse the holy spot and after replenishing our water supply decide to climb Mount Moses. The ascent is hot and steep. The upper part is a staircase which a monk had vowed to built. Supposedly it has 3400 steps but I only count 798. On top there is a church, a monastery and a toilet. The church is closed, the monastery covered in arabic graffiti and the toilet abominable. Supposedly you can look as far as the red sea and the tip of the Sinai peninsula from here but today is a hazy day. The next peak is Djebel Catherine, which is 350 m higher. In 1981 it was still occupied by the Israelis and therefore not accessible to us.

On the top of Mount Musa

On the way down we hope to refill our canteens at the wells of Moses. We find a tiny oasis with three cypress trees but no well. It might be hidden in one of the buildings. From far away the place looks inviting, but at a closer look it is disfigured by piles of old cans, toilet paper and human shit. So we go back down to the monastery to get water. We arrive with a big group of noisy german package tourists. Then another group of visitors arrives in a couple of taxis. They are actually allowed in. One has a diplomatic passport and has arranged everything. They have paid 160 pound for the taxi ride.

The spring of Moses

And then happens what I would have least expected to happen here…. it starts to rain. Not a lot, but it is unpleasant to feel big, cold drops hit the skin.

The garbage at the well of Moses

We get some undefinable potato dinner in the cafeteria and ask guardedly if somebody will go down to wadi Feiran or the main road tomorrow. Eventually a guy arrives and offers us a ride for 25 pounds each. To much for a student and bartering doesn’t bring the price down. We will have to see what the next day will bring.

After breakfast the next morning we buy some cans, bread and snacks and also a jerry can, which we fill with water for the way back. However, on the hot walk to the intersection at the entrance of the village, where we hope to hitch a ride, we realize that we might have to carry this heavy can for the next days.

Our waiting spot at the entrance of the village

We wait for a long time but there is only a single car the other way. That is not really a surprise. We did not see a functioning car somewhere in the village or at the monastery. Eventually a police jeep passes by, and upon noticing us, turns around and stops. He doesn’t mind to bring us to the military checkpoint at the entrance of the valley where we stopped on our way in.

We are quite glad that we don’t have to go further with him. The driver seems to confuse the sand-covered paved road with a race-track. He moves with a speed of up to 130 km/h and drifts through the sandy curves while we are tossed around in the back.

At the post our passports are checked kindly and we can sit in the shade, but there is no traffic. In two hours only a french camper passes in the opposite direction. Finally a big Dodge pick-up storms in. The guard talks to the driver and they tell us that we can have a lift to Abuo Rodeis for two pounds. We are even ushered into the front seat.

Wadi Feiran

The driver is a funny and talkative sort of person. He whistles, laughs and sings, lets the truck swing, stretches his head out of the window to talk to the people in the back and shouts at everything moving close to the road, including camels and goats. To show the merits of his vehicle he drives in the sand even when the road is good and takes every bump he can find to demonstrate the quality of the suspension. The route passes down a Wadi full of the famous Manna-trees, which provided the wandering Israelits with their food. On both sides sheer cliffs and rock towers in many colours. This time we can enjoy the view of the oasis of Peiran covered in dense green topped by palm trees. Again our driver shouts at everybody and some guys join us and hand out delicious dried plums. At a snack bar he buys coke for everybody and refuses any payment.

At about half past two we arrive in Abou Rodeis. It does not look best for the continuation of our trip since all the traffic is south-bound. A big group of Bedouins is already waiting for a lift north. Finally a big open bed truck stops and offers to take us to Suez. We have to share the cabin with three others. My butt will still hurt days after from sitting on the hard middle console. The military checkpoints are no match for our driver. He just lets his truck push aside the empty oil barrels on the track designed to stop the traffic and carries on with the words "I Palestinian, not Egypt”. Angry guards stay behind. Only one seems to note down the license plate.

Our driver to Suez

The sandy track is in a bad shape. All traffic leaves behind a long cloud of dust. In parts the road winds up in steep turns. A new road is already under construction. Along the whole route we pass stranded trucks, some stuck in the sand, others with white or dark smoke leaving the engine. Once we stop and hand out water. For one truck there is too much water – in an oasis he is stuck in a ford. Our driver has some problems with the gear box…. the second does not want to go in.

A truck is stuck in the ford

It gets dark when we get close to the Suez canal. We stop at a snack and have tea. Our driver wants to leave us here, but the owners of the snack convince him to take us on. But now the trucks’ lights do not work any more. That wouldn’t be such a problem because here most drive without lights anyway, but the flashlight they use to warn each other doesn’t work either. The driver removes the dashboard. The light of matches reveals a chaotic jumble of wires, solder joints and taped connections. When we produce our torches he have won his eternal gratitude. After some fumbling he finds two wires, twists the ends and seals them with some old tape from another part of the jumble. The lights work again.

After some erratic driving in the desert we reach a chaotic military convoy. It turns out that this is the waiting queue to cross the pontoon bridge over the canal. While we wait somebody suddenly appears with a pasta dinner for all of us from the military’s kitchen. We have not eaten all day and devour it quickly without thinking where it came from. It does not taste so bad. In the meantime the driver and his son repair something under the truck in the light of our torches.

The road to Suez

After 2 hours of waiting we can watch an organised retreat of the egyptian army in peace time. Most of the vehicles around us are in a deplorable state. One only moves in jumps. Others are pushed to start before dying again. There is no order at all. Everybody tries to be the first. An officer wearing a red barrett tries to organise the chaos but is in danger to be run over. Horns are blown, lights are flashed, people shout and scream. Diesel exhaust and dust fills the night air. In the middle, our truck, moving exceptionally cautious. Eventually we reach the pontoon and our driver eases the truck very slowly across. It now turns out that they had tried to mend the brakes when they worked under the truck. To make them work our driver is pumping the break pedal in wild desperation. He even has to resort to the hand brake once and we are almost thrown against the wind screen.

So we are kind of glad that we can say farewell to these good people at the next intersection and look for another ride for the remaining few kilometres into Suez. Eventually another pick-up takes us and in the town centre we find a collective taxi to bring us to Cairo the same night.

The train from Cairo to Alexandria.... topic of another story

Link to the previous post